Stop Re-Traumatization in Children’s Services and Schools

July 2022

My involvement with the public school system began when I went off to kindergarten at age 5. It ended when I was “exited” from the public school system in my 8th grade year and sent to a private facility for “delinquents”

My professional beginning was as a teacher, then a Principal, then as a School Improvement Officer working for the state of Texas. I went back to school when I was 38 to become a Social Worker because what I observed were schools “putting out” children who were not being successful in school by blaming the student and taking no responsibility for the child’s failure. That was the population I wanted to work with. Children who presented as challenging like me that was the result of untreated trauma.

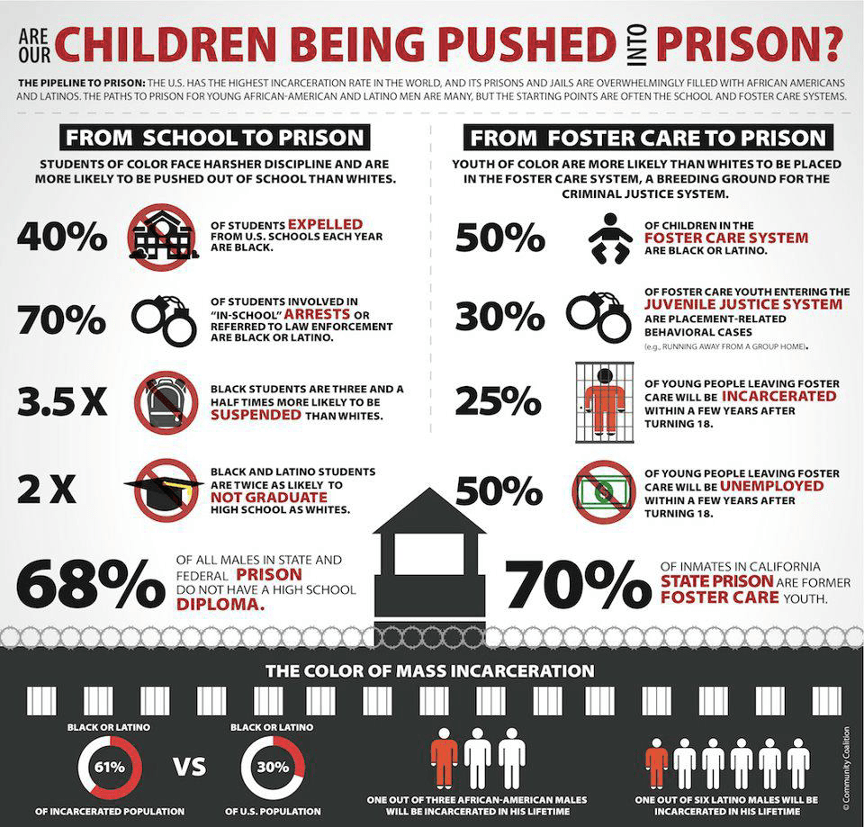

We have for the past two decades heard and read about the studies that show the School to Prison Pipelinethat starts with children’s failure in school. See the graphic depiction of the findings on page 4.

There have been federal efforts made over the past two decades to try to stop blaming the student for his/her failure. We passed Public Law 94-142 and said to schools, they need to provide a positive educational experience for children with special learning needs in the least restrictive environment in which s/he can succeed. The law never said put all special education students in regular classrooms. The intent of the law was positive – help all students succeed in the least restrictive environment.

Leave No Child Behind again was an effort to say to schools that the job of the school is to help students learn and the way to measure if students learn is to use state-wide tests. Again, the intent was positive – help all children learn and succeed (don’t leave any child behind) and assess schools to be sure the students in that school are in fact learning.

The lesson from these multi-decades efforts is you cannot legislate student success. It is the leadership at the state and even more so at the local school district/building level that must embrace the belief that the role of the school is to help all children succeed.

If the leadership of schools holds that belief, then it becomes their job to work with teachers to help them also come to embrace the belief that their job as a teacher is to help all students succeed in the classroom – to learn.

While this is an easy belief to profess, it is incredibly difficult to operationalize.

Schools do not change practice easily. What they do is find easy ways to eliminate any student that is not obedient and learning and then show the success of the remaining students.

As the chart on page 5 shows, schools “put out” students who are having difficulty learning in a traditional model, so their graduation rates look better.

Why should this be a concern for those of us who work in child and family services?

First schools fail challenging, traumatized children which adds to the trauma. Then when we get them in care, we send them back to the same school situation producing the same results.

Having worked in foster care, group care and residential I can personally report that the schools make achieving success with traumatized children more difficult because they want children to either be 100% complaint, respectful and obedient or they want them out. It’s easy and it’s the child’s fault not the adults.

Schools have demonstrated they do not have the willingness to change how to work with traumatized children in a school setting – but they could and under the law they are supposed to.

Those of us who work in child and family services need to engage the public school system (s) that serve our children to help them better understand how to help traumatized children become successful.

What schools are successful in is helping unsuccessful students go to prison.

We need them to change that process to helping them succeed.

But schools will say they don’t have the resources to help them. Then schools need to partner with child and family services and mental health to bring those resources to help traumatized children not banish them.

This requires social services and mental health and schools to come to the table and together figure out ways to help these children stay in school and experience success.

The cost of keeping someone in prison for one year is the US in 2015 was from $ 17,000 to $ 70,000 (Vera.org). The average is $ 35,347 (2019)

If the school – social services – health – mental health and law enforcement worked to decrease the prison population by 100 inmates that would free up $ 3,500,000 to re-invest in keeping future generations out of prison.

Here is the core fact:

When children come from traumatized families and neighborhoods into school, care and/or treatment they behave the way they always did – their normal.

Any they seek to recreate what was normal for them – I was an abused and school bullied child. I re-acted with anger and non-compliance with adults in authority positions.

No one in school or anywhere else ever asked me what that was about. They simply said they would not tolerate it and put me out – further retraumatizing me.

I was then put in residential care where the rule was comply or be punished. I graduated 4 years later angrier at adults who inflicted pain and was more non-compliant. It would be several years later (after several disastrous years failing in college) that one person helped me see I had untreated trauma and that there was a path to success that I could take. It was an amazing healing journey.

He asked me where all that anger was coming from and worked with me until I could not just express it but more importantly understand and accept it.

If the school had seen and asked what my behavior was about rather than just try to punish me into compliance the road would have been more successful earlier.

While this is a newsletter focused on thinking outside the box for human service leaders, what I challenge human service leaders to do is engage the schools as a critical partner who can help or hinder our helping children recovery from trauma and not be retraumatized. Feel free to share this issue with them.

=============================================================

11 FACTS ABOUT HIGH SCHOOL DROPOUT RATES

Published by Do Something!

1. Every year, over 1.2 million students drop out of high school in the United States alone. That’s a student every 26 seconds – or 7,000 a day.[1]

2. About 25% of high school freshmen fail to graduate from high school on time.[2]

3. The U.S., which had some of the highest graduation rates of any developed country, now ranks 22nd out of 27 developed countries.[3]

4. The dropout rate has fallen 3% from 1990 to 2010 (12.1% to 7.4%).[4]

5. The percentage of graduating Latino students has significantly increased. In 2010, 71.4% received their diploma vs. 61.4% in 2006. However, Asian-American and white students are still far more likely to graduate than Latino & African-American students.[5]

6. A high school dropout will earn $200,000 less than a high school graduate over his lifetime. And almost a million dollars less than a college graduate.[6]

7. In 2010, 38 states had higher graduation rates. Vermont had the highest rate, with 91.4% graduating. And Nevada had the lowest with 57.8% of students graduating.[7]

8. Almost 2,000 high schools across the U.S. graduate less than 60% of their students.[8]

9. These “dropout factories” account for over 50% of the students who leave school every year.[9]

10.1 in 6 students attend a dropout factory. 1 in 3 minority students (32%) attend a dropout factory, compared to 8% of white students.[10]

11.In the U.S., high school dropouts commit about 75% of crimes.[11]

1. Miller, Tony. "Partnering for Education Reform." U.S. Department of Education. Accessed February 18, 2015. . ↩︎

2. Silver, David, Marisa Saunders, and Estela Zarate. "What Factors Predict High School Graduation in the Los Angeles Unified School District." Attendance Counts. Accessed February 18, 2015. . ↩︎

3. BANCHERO, STEPHANIE. "High-School Graduation Rate Inches Up." The Wall Street Journal. Accessed February 27, 2014, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887323301104578256142504828724. ↩︎

4. U.S. Department of Education. "Fast Facts: Dropout Rates." Institute of Education Sciences. Accessed February 26, 2014, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=16. ↩︎

5. Resmovits, Joy. "Graduation Rate Hits Record High For High School Students: Government Report." The Huffington Post. Accessed February 26, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/01/22/graduation-rate-record-high-school-students_n_2522128.html. ↩︎

6. Cheeseman Day, Jennifer, and Eric C. Newburger. "The Big Payoff: Educational Attainment and Synthetic Estimates of Work-Life Earnings." United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 26, 2014, https://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/p23-210.pdf. ↩︎

7. Layton, Lyndsey. "National public high school graduation rate at a four-decade high." Washington Post. Accessed February 26, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/national-high-school-graduation-rates-at-a-four-decade-high/2013/01/21/012cd7da-63e7-11e2-85f5-a8a9228e55e7_story.html. ↩︎

8. Balfanz, Robert, and Nettie Legters. "LOCATING THE DROPOUT CRISIS ." Center for Social Organization of Schools at Johns Hopkins University's School of Education. Accessed February 26 26,2014, http://www.csos.jhu.edu/crespar/techReports/Report70.pdf. ↩︎

9. Sparks, Sarah D.. "Study Points to Fewer 'Dropout Factory' Schools." Education Week. Accessed February 18, 2015. . ↩︎

10. Balfanz, Robert, and Nettie Legters. "LOCATING THE DROPOUT CRISIS ." Center for Social Organization of Schools at Johns Hopkins University's School of Education. Accessed February 26, 2014, http://www.csos.jhu.edu/crespar/techReports/Report70.pdf. ↩︎

11. Smiley, Travis. "Fact Sheet: Is the Dropout Problem Real?." Travis Smiley Reports. Accessed February 26, 2014. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/education-under-arrest/fact-sheet-drop-out-rates-of-african-american-boys/.

LEADING FROM OUTSIDE THE BOX is a monthly newsletter for human services leaders.

Its purpose is to challenge your thinking and help you improve organizational and outcome performance.

To receive your copy free, simply email Jeff Bormaster and ask to be added to the mailing list. Feel free to share these newsletters with other human services leaders, simply include the contact information.

You can read previous issues of Leading Outside the Box at www.jeffbormasterconsulting.com/topics