Helping Youth Succeed – It Starts with Helping Staff Succeed

The federal Children’s Bureau (CB) through the Adoptions and Safe Families Act (ASFA) set standards for the child welfare field. They want states, and in turn counties and private providers, to operate in a way that assures that children who come to the attention of the “system” are not further abused or neglected.

This is a glass is half-empty model that we have used for decades – to not have them further harmed (negative). This can easily be flipped to a glass is half full model – “helping children succeed in exiting the system to success in life-

They also recognize that the “system” is not the best parent and children deserve the opportunity to grow up in a caring safe family, their own or a guardian/adoptive family.

ASFA also recognizes that all children coming into the out-of-home care system have been traumatized and that for successful recovery to occur service providers must assess and treat the underlying trauma, both in the child and often in the family when we hope to return the child to them.

Over a decade after ASFA was first announced and the first reviews of states’ performance were done, the system has made some changes.

First, the public sector is begun assessing referred children to determine if they can safety remain in their home setting with services. The competency of the staffing doing the assessment and the validity of the “tool” being used needs to be assessed. A check the box approach is not a clinical assessment. A clinical assessment requires a clinically trained social worker not a worker with a bachelor’s degree.

Second, there are now more children being served with in-home services including with relatives (most often grandparents) as opposed to being removed.

The problem is too many children are still being left in unsafe homes, with questionable relatives and are being re-traumatized or left untreated for trauma.

Then when it is clear the child cannot be served in-home, we use a “failure model” to determine what services the child and family requires. It is also a financially driven model (though we would never admit that). We ask – what is the least amount of service (least cost) we can provide this child and then hope it works.

And when it doesn’t work the system repeatedly says it wasn’t a right match so let’s try another family member (most often the grand parents who are in fact the parent of the parent of the child who was abused or neglected – there is a multigenerational trauma problem that is being ignored) or another foster home then group home then finally residential services.

The consequence is these children who have been abused and neglected and have experienced trauma that is left untreated end up in residential care after months to years of multiple failed placements which have only further retraumatized the child.

I have had residential programs I have worked with report an average of 12 – 20 failed placements before they are placed in residential. That proves the intake assessment for appropriate level of care is invalid!

Every public child welfare system should do a snapshot of all children in residential at a moment in time and for each resident count the number of failed interventions and placements each child had before being placed in their current residential setting.

Then we ask residential programs to do trauma recovery in a short amount of time giving no acknowledgement of the amount of time the child spent being abused and traumatized and experiencing repeated failure in the system before coming into residential.

If the public child system really wanted shorter residential stays, then it would be doing clinical assessments of the level of trauma at intake and identify what executive functioning skills the child lacked.

As ASFA and all subsequent federal child welfare legislation makes clear - all children coming into the child welfare system have been traumatized and require trauma treatment.

Foster care doesn’t do that nor does relative placement. Few residential programs have trained all staff to write trauma recovery treatment plans nor do effective trauma recovery work – they still operate in a traditional adult control model using level and point systems (punishment) as the change tool. That approach just does not work for the most challenging children.

And we need to have the care provider teach the missing executive functioning skills. Two of the most common executive functioning skills these children placed in residential care lack are emotional regulation and lack of impulse control.

We know why this “failure model” is not working.

It is time to change practice so our children in care can be more successful.

The challenge is getting child welfare leaders to make the commitment to move from the long standing “punishment and failure model” that is not working to a different model.

What we know about the outcomes of our current foster care model is:

Children’s Bureau Express, March 2015

Children, youth, and families who are homeless or who have experienced homelessness must often deal with complex traumatic issues including domestic violence, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, food insecurity, illness, and the stresses of unstable housing and changing schools. For children and youth, these traumatic experiences, if left unaddressed, can lead to negative long-term consequences such as depression, anxiety, attachment issues, substance abuse disorders, and other mental health problems. Foster care is not addressing trauma.

Scientific American, October 16, 2014

Researchers have long found that punishment-based strategies tend to be less effective than reward-based strategies for lasting behavioral change, in part because they teach people what not to do but not what to do. Second, studies indicate that highly confrontational therapeutic approaches are rarely effective long term.

Association of Small Foundations, April 2008

Every year, about 20,000 young people exit or “age out” of the foster care system, typically at age 18. The system, and whatever it provided, simply disappears. These youth are on their own, virtually penniless, with no place to call home. How do former foster care kids fare as adults? Four years after “aging out” of the system:

· 25% have been homeless;

· less than half have graduated from high school;

· 42% have become parents themselves; and

· more than 80% are unable to support themselves.

A recent study found that adults who have been in foster care suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder at twice the rate of US combat veterans. More than half experience serious mental health problems.

Jim Casey Initiative

These young people experience very poor outcomes at a much higher rate than the general population:

▪ More than one in five will become homeless after age 18 1

▪ Only 58% will graduate high school by age 19 (compared to 87% of all 19-year-olds) 2

▪ 71% of young women are pregnant by 21, facing higher rates of unemployment, criminal conviction, public assistance, and involvement in the child welfare system 3

▪ At the age of 24, only half are employed 4

▪ Fewer than 3% will earn a college degree by age 25 (compared to 28% of all 25-year-olds) 5

▪ One in four will be involved in the justice system within two years of leaving the foster care system 6

1 Casey Family Programs. (1998). Northwest foster care alumni study. Seattle, WA. p. 37

2 Courtney, M.E., and Dworsky, A. (2005). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 19. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall Center for Children. p. 22

3 Pecora, P.J., Kessler, R.C., Williams, J., O’Brien, K., Downs, A.C., English, D., White, J., Hiripi, E., White, C.R., Wiggins, T., and Holmes, K. (2005). Improving family foster care: Findings from the Northwest foster care alumni study. Seattle, WA: Casey Family Programs. p. 1Courtney, M.E., Hook, J.L., and Lee, J.S. Distinct Subgroups of Former Foster Youth During the Transition to Adulthood: Implications for Policy and Practice. Chicago: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

4 Pecora, P.J., et al. (see note #3)

5 Pecora, P.J., et al. (see note #3)

6 Courtney, M.E., Dworsky, A., Terao, S., Bost, N., Cusick, G.R., Keller, T., and Havlicek, J. (2005). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 19. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall Center for Children. p. 61

Gary Grander in Huffington Post, July 28, 2013

A study issued in May 2013 by the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative -- shows that, on average, for every young person who ages out of foster care, taxpayers and communities pay $300,000 in social costs like public assistance, incarceration, and lost wages to a community over that person's lifetime. Do the math and you can conservatively estimate that this problem incurs almost $8 billion in social costs to the United States every year.

Rita Sorenson on CNN April 17, 2014

In 2012 there were 3.3 million reports of violence against children resulting in 400,000 children being placed in foster care:

· 60,000 of which were permanently taken away from their family

· 23,439 aged out of foster care

· 1 in 5 will become homeless after age 18

· Only 1 in 2 will be employed at age 24

· Less than 3% will earn a college degree

· 71% of young women will become pregnant by age 21

· 1 in 4 will experience Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, twice the rate of United States war veterans

I could go on but those of us that work in the field, we know the unfavorable outcomes for youth emancipated from foster care.

If the system isn’t working for these youth the question you must ask is, why?

We know why. Our system of treatment for in-home and for out-of-home is based on a long-standing model premised on the false belief that if you threaten enough negative consequences that youth will change their behavior. While that may be true for a few in the short run, it in fact long term results in a population that:

· Doesn’t trust adults

· Has no educational future

· Under-employed or unemployed

· Suffers from untreated trauma

· Becomes a long-term cost to the public

Our traditional model of intervention including many “evidence-based practices” that do not teach the executive functioning skills such as impulse control, as the system is run using external “other control” by the adult staff rather than teaching Executive Functioning Skills these youth lack.

You can punish a child for not having a skill forever and that youth will still not learn that skill.

You learn skills by being taught those skills not by being punished for not having that skill.

I can give personal testimony to that truth. When I was sent to a military style residential placement for 4 years of high school, they told us when to get up, what to wear, what we can do and when we did not do exactly as instructed, we were increasingly punished on the belief that if the punishment becomes too great the youth will comply aka change. What they did not understand and still today many don’t grasp is that that punishment model does not teach “self control.” After I left that facility, I was out-of-control for several years because no one taught me the skills of self-control; they simply controlled me.

Our intervention programs must become willing to operate on a different model – one that allows youth to learn and experience increasing self-control not under threat of punishment but as a success-focused process that helps them learn that they can make choices and those choices will lead to their success or failure.

But before you can begin to implement this model with your clients you must first implement it with your staff. The principle of parallel process tells us that if you want staff to work in a different non-punitive model, you must first implement the same model with your staff.

See Appendix A

What does this require of organizational leaders?

1. You must model with staff what you them to do with clients.

2. Implement from the top down a success-focus model that will help staff then clients be successful.

3. Stop using a coercive threat of punishment model with staff. End Progressive Discipline as it only builds hostile relationships between staff and management and creates a “fear” environment that also leads to trauma.

4. Identify and treat trauma and vicarious trauma in staff then teach staff the skills to treat trauma in clients.

5. Teach staff how to assess executive functioning skills and teach those that clients are lacking.

Step 1: It starts with using the non-punitive success focused model ourselves as the senior management. If you don’t model the behavior, you want staff to do then any change will fail with staff.

Does the success focused model work?

I have taught and evaluated 30 courses – The evaluations from 701 participants:

1. Did you learn/ have reinforced knowledge and skills that will help you be a more success-focused supervisor?

701 0

Yes No

2. Can you put into practice what you have learned in this course?

701 0

Yes No

Step 2: Once you put the success focus in place with staff, then you train line staff to put it in place with clients.

Step 3: Teach staff to assess and teach executive functioning skills to clients. This must include clinical staff AND line staff in residential settings, foster parents and kinship caring family members.

It is the adults (starting with senior management) in the organization who lead the way (parallel process) to lay the foundation of successfully doing it with clients.

It’s your decision – is your job to help staff then clients succeed or simply behave as you always have, don’t change and complain that staff can’t deal with change. They can’t deal with change because senior management holds on to the status quo.

=============================================================

LEADING FROM OUTSIDE THE BOX is a monthly newsletter for human services leaders. Its purpose is to challenge your thinking and help you improve organizational and outcome performance.

To receive your copy free, simply email Jeff Bormaster at [email protected] and ask to be added to the mailing list.

Feel free to share these newsletters with other human services leaders, simply include the contact information.

You can read previous issues of Leading Outside the Box on my website, Jeffbormasterconsulting.com.

Appendix A

Parallel Process

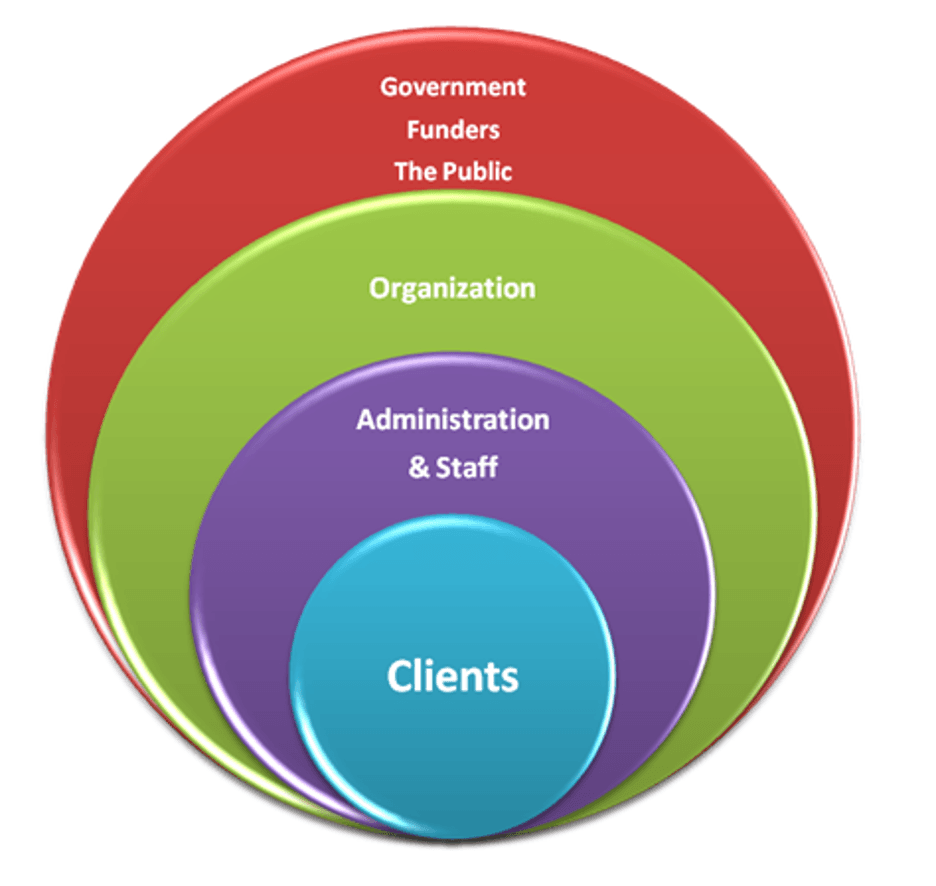

Our systems are all interconnected and interactive, each one nested within the other. In this image we only have four layers of these nested systems but remember that the layer labeled “government, funders, and the public” is itself nested within larger social and global systems. Therefore, everything that happens to one system is likely to be reflected in all the others.

The concept of parallel process taken out of the individual context and applied to organizations is a useful way of offering a coherent framework that can enable organizational leaders and staff to develop a way of thinking “outside the box” about what has happened and is happening to their service delivery systems, based on an understanding of the ways in which trauma and chronic adversity affect human function.

Parallel process has been defined as what happens when two or more systems – whether these consist of individuals, groups, or organizations – have significant relationships with one another, they tend to develop similar affects, cognition, and behaviors, which are defined as parallel processes …. Parallel processes can be set in motion in many ways, and once initiated leave no one immune from their influence.

Clients bring their history of traumatic experience into the social service sectors, consciously aware of certain specific goals but unconsciously struggling to recover from the pain and losses of the past. They are greeted by individual service providers, subject to their own personal life experiences, who are more-or-less deeply embedded in entire systems that are under significant stress. Given what we know about exposure to childhood adversity and other forms of traumatic experience, the majority of service providers have experiences in their background that may be quite similar to the life histories of their clients, and that similarity may be more-or-less recognized and worked through.

The result of these complex interactions between traumatized clients, stressed staff, pressured organizations, and a social and economic environment that is frequently hostile to the aims of recovery is often the opposite of what was intended. Staff in many treatment programs suffer physical and psychological injuries at alarming rates and thus become demoralized and hostile. Their counter-aggressive responses to the aggression in their clients helps to create punitive environments. Leaders become variously perplexed, overwhelmed, ineffective, authoritarian, or avoidant as they struggle to satisfy the demands of their superiors, to control their subordinates, and to protect their clients. When professional staff and nonprofessionally trained staff gather together in an attempt to formulate an approach to complex problems, they are not on the same page. They share no common theoretical framework that informs problem-solving. Without a shared way of understanding the problem, what passes as treatment may be little more than labeling, the prescription of medication, and behavioral “management”. When troubled clients fail to respond to these measures, they are labeled again, given more diagnoses and termed “resistant to treatment”.

In this way, our systems inadvertently but frequently recapitulate the very experiences that have proven to be so toxic for the people we are supposed to help. Just as the lives of people exposed to repetitive and chronic trauma, abuse, and maltreatment become organized around the traumatic experience, so too can entire systems become organized around the recurrent and severe stress of trying to cope with a flawed mental model based on individual pathology, that is the present underpinning of our helping systems. When this happens, it sets up an interactive dynamic that creates what are sometimes uncannily parallel processes. The result can be seen in the chart on the next page.

Bloom and Farragher, Destroying Sanctuary: The Crisis in Human Service Delivery Systems

LEADING FROM OUTSIDE THE BOX is a monthly newsletter for human services leaders.

Its purpose is to challenge your thinking and help you improve organizational and outcome performance.

To receive your copy free, simply email Jeff Bormaster and ask to be added to the mailing list. Feel free to share these newsletters with other human services leaders, simply include the contact information.

You can read previous issues of Leading Outside the Box at www.jeffbormasterconsulting.com/topics